An aim of the Agile Opera Project was to study the business layer of Chamber Made Opera (CMO)—how the company actually gets things done—as opposed to business as a commercial way of operating. Little is known of how small-to-medium arts (SMA) organisations actually operate. This is despite the last 20 years having seen operational aims foisted on the sector, changing foci demanded by governments and funding agencies, and technologies grafted onto companies. How do they actually operate behind the scenes of their annual cycle of public presentations? And why is this worth knowing?

A criticism of the managerialist approach is the absence of “domain knowledge” (Crittenden, 2009[1]). The managerialist assumption is that a manager can manage anything. Knowledge of what the workers do and knowledge of the content of their jobs is unnecessary. Management can be grafted onto any situation, relying predominantly on metrics as the driving organisational determinant (Orr & Orr, 2016[2]).

The Rhythm of a Year, as a substudy of the Agile Opera Project, is based on observations of Chamber Made Opera operations over the course of the project and discussions from the Microlabs which ran throughout 2015-17. This substudy seeks to understand the existing networks of the company and the effort required to sustain organisational infrastructure while delivering productions.

An indicative year

In general, the primary period for production in the Australian arts sector spans the 46 weeks between February and mid-December. Annual presentation programs, major festivals, funding rounds, workshops and creative development take place during this period. Other factors further reduce this primary production period. Most companies have limited or no local activity over the summer break spanning mid-December to the end of January (six weeks), unless they are involved in festivals held during this period (e.g., Sydney Festival; Woodford Folk Festival; MOFO, Tasmania; Midsumma Festival, Melbourne). Many companies, when not part of a capital city or major arts program, will avoid presenting works at the same time (two to three weeks). For companies not involved in the summer festival season, February is often a ‘start-up’ month for pre-production, workshops, planning, office or maintenance activities that lead into the first half year of annual program.

These factors serve to reduce annual production schedules to an average of 38 weeks, which explains why the arts calendar can sometimes be extremely crowded. An indicative timeline for one Chamber Made Opera project mapped over this 38 week period reveals a compressed and pressured rhythm (Infographic 1).

Exceptions to this indicative annual schedule extend the annual performance calendar and, therefore, increase pressure on the production schedule. For example, companies may elect to tour or travel to the northern hemisphere, commonly during the period January/mid-February. For other companies, involvement in a major festival held during February/March (Perth International Festival; WOMAdelaide; Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras; Adelaide Festival of the Arts; Ten Days on the Island, Tasmania) transform the late-December/January to a period dedicated to final production tasks.

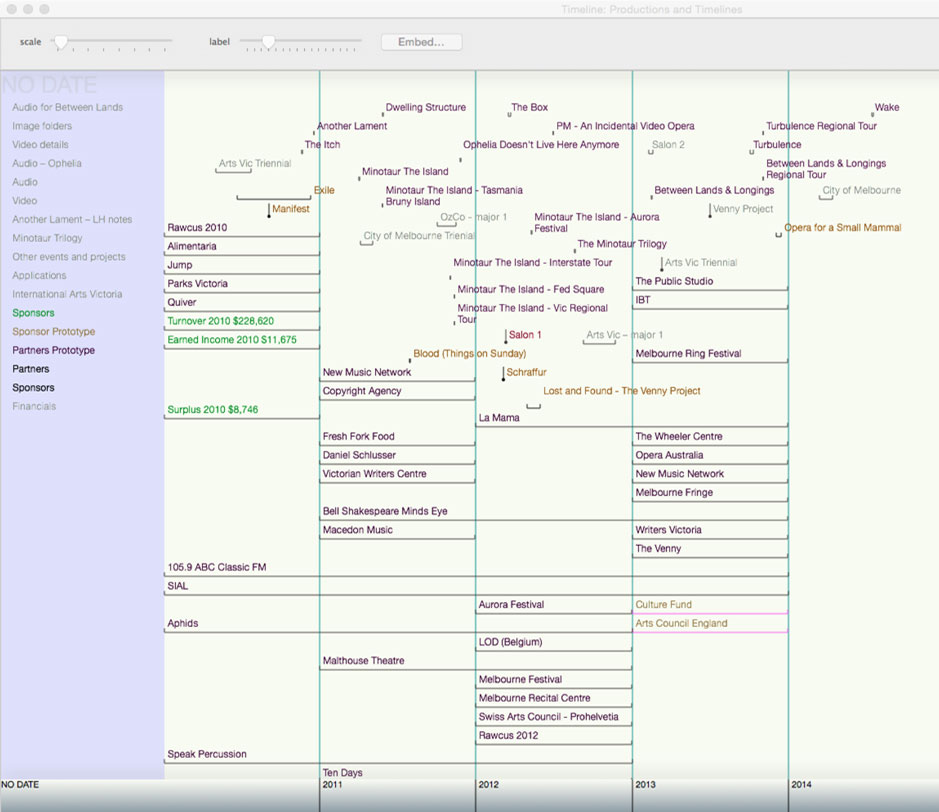

This 38 week timeline compared to an actual timeline from CMO (Infographic 2: Timeline – 2010-2014) reveals a timeline even further pressured and congested. This diagram shows productions and key relationships serviced by the company to support its activities. The image is a screenshot from Tinderbox (Eastgate), used to collect and collate data for the analysis.

Life cycle of a programme or project

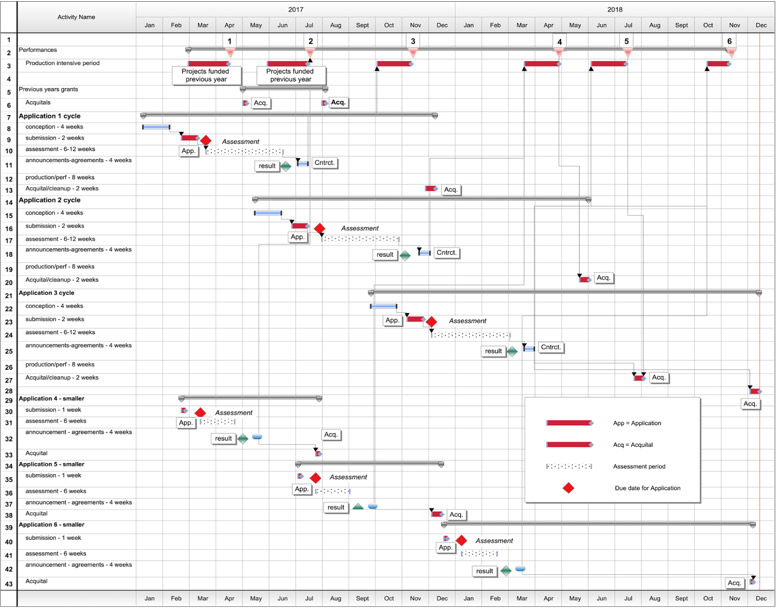

The Rhythm of a Year considers a 31-week model for the life-cycle of a funded project. This model is based on six project applications (three major and three minor projects) selected for comparison as they follow similar component stages.

Components stages of the life-cycle are listed in Table 1 (below) presenting a complex interlocking and overlapping of operational phases. The pressures associated with this complex life-cycle are mitigated for companies securing triennial (rather than annual) funding agreements. Other sponsorship/partnerships and artistic production activities are not included in this life-cycle.

Table 1: Component stages of a 31-week model for the life-cycle of a funded project

| Component stages | Approx. duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Conception-application | 4 weeks | Although experienced arts workers can produce applications more quickly, this stage is a nominated period in which the preparation of the application is afforded maximal focus by key company personnel. Ideas are forming in the background over a longer period, but the urgency of a pending deadline begins to pull focus. |

| Submission | 2 weeks | This is an intense period in which budgets, letters of support, venue agreements, ‘pencil’ bookings made and artist availability confirmed. It is estimated that this period requires three people working for two weeks. Government and most philanthropic organisations now have an online grant submission process which has reduced the amount of paper handling but can cause stress if online systems cannot cope with applicant traffic on submission due dates. |

| Assessment | 6-12 weeks | This time involved submission of the application and the next stage is dependent upon the funding source. Typically, this stage involves applications being read by assessors, panel-peer assessment meetings and final sign-off by the funding body. |

| Announcement-Agreements | 4 weeks | Announcements are generally made in the form of a press release. Contracts and agreements are issued and signed prior to payments. At this point the project is ‘live’ and artist and arts worker availability can be confirmed. Alternatively, when full funding is not received, projects are re-configured, delayed or cancelled. |

| Production-performance | 4-8 weeks | When compared to some overseas arts sectors, Australia’s SMA companies operate on very short production-performance timelines. |

| Acquittal and clean-up | 1 week | This phase involves general post-production tasks and activities, acquittal reports for funding bodies, and collation and review of performance documentation. |

Explanation of component stages and assumptions

To capture the forward planning required by companies to manage funding activities, it is necessary to examine a two-year period. The application process to secure project funding demands sufficient time between application, announcement and commencement of the production schedule.

An annual program is often funded in two parts. Funding for projects in the period Feb–June are generally secured the previous year (in diagram see projects 1 and 2), while funding for projects in the period July-December are generally sourced from applications submitted earlier the same year. This funding application timeline presents risks to companies funded on an annual rather than triennial basis.

The application dates used in Infographic 2 were drawn from due dates for the Australia Council, Creative Victoria, The Myer Foundation and The Ian Potter Foundation.

Observations about the diagram

Over a two-year period, 15 periods of intensive work are identified and defined as times devoted to application writing and acquittal reports. These periods range from one to three days for an acquittal report, to two-weeks for a major application during which the application is a critical major focus for the company.

The solid black lines show the full period of a grant (around 31 weeks) that usually stretches over two calendar years.

Analysis: Chamber Made Opera Annual Reports (2010-2015)

An analysis of CMO Annual Reports for 2010-2015 revealed much about the extent of their work in raising funds to mount productions. The scope includes: government (federal, state and local), private, philanthropic, project, business and sponsors. Each of these funding connections demand at least one individual contact with whom a relationship must be developed. This results in the CEO of CMO having approximately 30 key external people on their contact list, supported by a five-member board and three to five staff members. In addition to these key contacts, up to 70 artists are involved over this period.

Table 2: Key funding contacts sustained by CMO (not including artists)

| Component stages | Approx. duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Conception-application | 4 weeks | Although experienced arts workers can produce applications more quickly, this stage is a nominated period in which the preparation of the application is afforded maximal focus by key company personnel. Ideas are forming in the background over a longer period, but the urgency of a pending deadline begins to pull focus. |

| Submission | 2 weeks | This is an intense period in which budgets, letters of support, venue agreements, ‘pencil’ bookings made and artist availability confirmed. It is estimated that this period requires three people working for two weeks. Government and most philanthropic organisations now have an online grant submission process which has reduced the amount of paper handling but can cause stress if online systems cannot cope with applicant traffic on submission due dates. |

| Assessment | 6-12 weeks | This time involved submission of the application and the next stage is dependent upon the funding source. Typically, this stage involves applications being read by assessors, panel-peer assessment meetings and final sign-off by the funding body. |

| Announcement-Agreements | 4 weeks | Announcements are generally made in the form of a press release. Contracts and agreements are issued and signed prior to payments. At this point the project is ‘live’ and artist and arts worker availability can be confirmed. Alternatively, when full funding is not received, projects are re-configured, delayed or cancelled. |

| Production-performance | 4-8 weeks | When compared to some overseas arts sectors, Australia’s SMA companies operate on very short production-performance timelines. |

| Acquittal and clean-up | 1 week | This phase involves general post-production tasks and activities, acquittal reports for funding bodies, and collation and review of performance documentation. |

Partnerships: a five-year outline

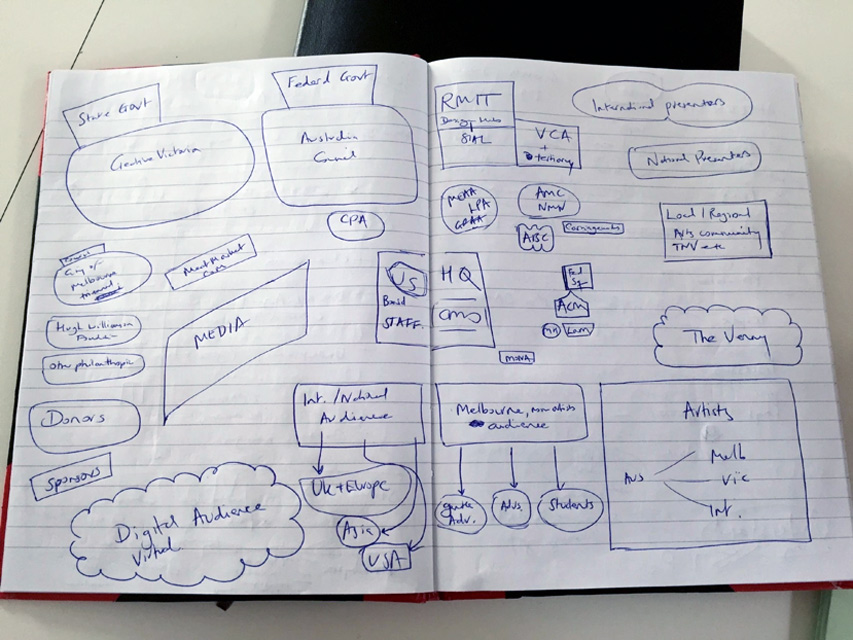

During a workshop in 2015 Tim Stitz sketched the partnership landscape for the company. Such diagrams are useful as they capture the myriad of relationships, sectors, individuals, groups held in mind by the company director. Each of these components occupies a place in attention of the company to varying intensity depending on the production/activity cycle of the company. For example during pre-production, audiences and artists would receive primary attention. During application stage partners and funding bodies would occupy focus. It is an ecology and demonstrates the multi dimensional landscape the company inhabits. The diagram depicts 39 separate categories of relationships across 12 distinct entities (See Table 2), and reveals the range of relationships that occupy the attention of even a small arts company in one year.

This is the landscape of attention: the sectors, places and people that the CEO and the company maintain on their radar, requiring light communication through to deep engagement through regular face-to-face meetings or detailed applications and reporting. Across this network of relationships, conversations and negotiations of varying degrees of intensity and significance must be fostered. The responsibility for sustaining relationships with donors, artists, sector peers and audience members continues, anchored at times by production dates, and at other times free-floating as part of the necessary survival strategy.

Table 3: Types and number of entities represented in the diagram of relationships drawn by CEO Tim Stitz.

| Component stages | Approx. duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Conception-application | 4 weeks | Although experienced arts workers can produce applications more quickly, this stage is a nominated period in which the preparation of the application is afforded maximal focus by key company personnel. Ideas are forming in the background over a longer period, but the urgency of a pending deadline begins to pull focus. |

| Submission | 2 weeks | This is an intense period in which budgets, letters of support, venue agreements, ‘pencil’ bookings made and artist availability confirmed. It is estimated that this period requires three people working for two weeks. Government and most philanthropic organisations now have an online grant submission process which has reduced the amount of paper handling but can cause stress if online systems cannot cope with applicant traffic on submission due dates. |

| Assessment | 6-12 weeks | This time involved submission of the application and the next stage is dependent upon the funding source. Typically, this stage involves applications being read by assessors, panel-peer assessment meetings and final sign-off by the funding body. |

| Announcement-Agreements | 4 weeks | Announcements are generally made in the form of a press release. Contracts and agreements are issued and signed prior to payments. At this point the project is ‘live’ and artist and arts worker availability can be confirmed. Alternatively, when full funding is not received, projects are re-configured, delayed or cancelled. |

| Production-performance | 4-8 weeks | When compared to some overseas arts sectors, Australia’s SMA companies operate on very short production-performance timelines. |

| Acquittal and clean-up | 1 week | This phase involves general post-production tasks and activities, acquittal reports for funding bodies, and collation and review of performance documentation. |

Contingent programming model

In this indicative life-cycle model, the lapsed time between an idea and it’s realisation is 31 weeks or more than half a working year. Artists and companies manage these timing issues by working up to three years in advance with a contingent programming model. SMA organisations divide the year into blocks and program options into any given time period (e.g., second half of next year, first half of following year). Given success rates of funding, it is unlikely that more than one project in a block will be funded and gaps can appear in a company’s program when project funding is wholly unsuccessful.

The contingent programming model means many ‘what ifs…’ or dependencies for multiple stakeholders. Company directors, artists, venues, equipment hire, travel arrangements, work dates, sponsor functions, printing, production are all placed on hold until funding is announced. And this is for one project of one company. The model rests across multi-year programs, three tiers of government funding (local, state and federal), and must incorporate the additional activities associated with philanthropic or private fundraising.

Multi-year funding reduces doubt, and allows a company to direct more focus and energy to creation of work. It is little wonder that corporate entities and major arts organisations regularly call for government policy and investment to provide certainty. While many lament the calls for the arts to operate like a business perhaps SMA organisations should join this chorus. As the business sector calls for ‘certainty’ to ensure investment, it is reasonable for those with even less resources to weather change to have the same certainty.

Conclusion

The now infamous National Program for Excellence in the Arts (NPEA) issue occurred during the course of the Agile Opera Project. While the negative consequences of the move by then Arts Minister George Brandis have all but played out, the sector demonstrated an extraordinary resilience and robustness, proving it already performs well above its government resource base. This is due to the ability of individual companies to create networks of support, and a large unfunded component of staff time. This is art funded by artists.

This is the environment into which new programs, new policies and new processes are introduced. Some level of resistance by SMA organisations is no surprise, as these companies are already stretched by the scale of their activities and often experience reform-fatigue. The increasing importance of metrics evaluation tends towards a one dimensional view of the sector, limiting the range of views represented and minimising perspectives from different vantage points. Understanding the volume and intensity of work and why disrupting this ecology might cause more than a ripple is critical to understanding the effect on a sector, in particular individual participant’s health and well-being.

We present three observations to describe the business layer of a SMA organisation:

- Minimum life cycle of a production: a critical path of 10 months from artistic concept to application and public production.

- Contingent programming: a consequence of the life cycle where projects are developed in parallel to avoid gaps in an annual program to cover funding applications that are unsuccessful.

- Small and sophisticated: small does not equate to simple. While the term large and complex is commonly applied to major organisations, this sector is characterised by small and sophisticated operations. A full analysis of annual reports reveals CMO sustaining partnership relationships with almost 60 different individuals and entities that collectively support the operations of the company. Complexity is not about scale, but rather how the parts interact and are supported by company staff and board members.

Business models have been thrust on the arts, underpinned by an assumption that arts organisations don’t have effective ways of operating. This is exemplified when business people with little or no arts knowledge are placed on boards to “help them out”. Yet, copying the dominant managerialist neo-liberal approaches is yet to be claimed a universal solution. By contrast, like other parts of the social sectors, it can be claimed that arts companies have unique and elegant ways of operating and surviving.

While this small substudy doesn’t propose a solution, it raises issues that argue the case for further research in this area.

[1] Crittenden, S. (Interviewer). (2009. MBA: Most bloody awful [Interview transcript]. Retrieved from ABC Radio National. Accessed, 1 December, 2016 from http://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/backgroundbriefing/mba-mostly-bloody-awful/3143174#transcript

[2] Orr, Y., & Orr, R. (2016). The death of Socrates: managerialism, metrics and bureaucratisation in universities. Australian Universities’ Review, vol. 58, no. 2, pp.15-25.

[3] This is a modest group of applications. Many companies make more applications in a two year cycle.